The twin screwed steamship the SS Tarpon was built in 1886, at Wilmington Delaware. She was originally christened the Naugatuck. She measured 130 feet overall with a beam of 26 feet and was powered by twin steam engines driving iron propellers.

Naugatuck’s owners sold her to Henry Plant, whose shipping empire at Tampa, Florida, was one of the largest conglomerates in the United States at the time.

In 1891, Naugatuck was sent back to her builders, who lengthened the vessel by 30 feet. Renamed Tarpon, she returned to Florida and was one of the dozens of Plant’s vessels used to transport troops and supplies to and from Cuba during the Spanish-American War.

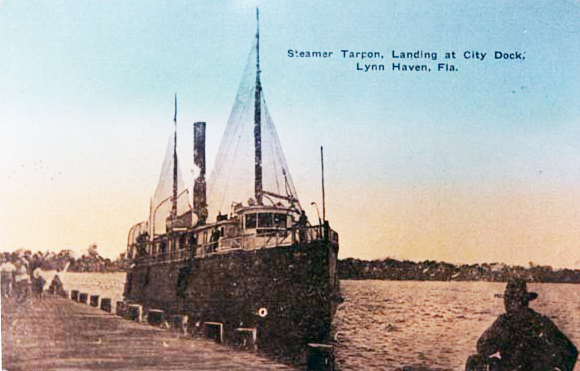

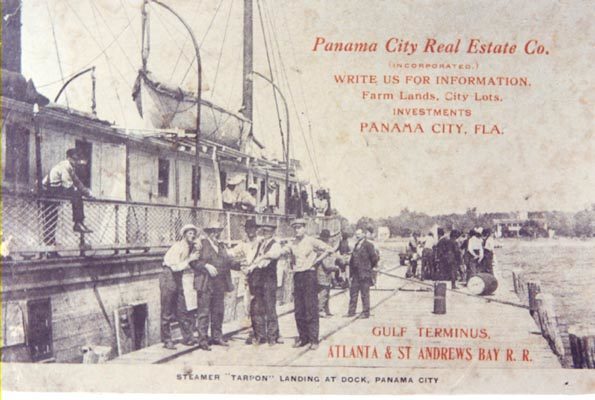

In 1902, the vessel was sold to the newly incorporated Pensacola, St. Andrews & Gulf Steamship Co. Captain Willis Green Barrow took command of the Tarpon and captained the ship for 34 years. The 160-foot, vessel plied the Gulf trade between Mobile, Pensacola, Panama City, Apalachicola, and Carrabelle. With W.G. Barrow as Captain, the vessel made a record 1,735 round trips, carrying passengers and goods.

At the turn of the century, there were few paved roads or bridges and commerce and communication between coastal communities was almost totally dependent on water-borne traffic.

Barrow and Tarpon maintained a strict schedule regardless of weather. In December 1922, Barrow celebrated 20 years as master of Tarpon by completing their 1,000th voyage to St. Andrew Bay.

An admiring local press estimated that the steamer had traveled a distance of 700,000 miles – equal to 28 times around the earth.

On August 30, 1937, the Tarpon was loaded in Mobile, with 200 tons of cargo and 31 people including the crew.

Weather forecasters predicted calm seas and Barrow placed the second mate William Russell at the helm. At 2 a.m., chief engineer Lloyd Mattair began to have difficulties keeping water out of the bilges due to a leak in the bow.

The Tarpon began to list to port. First mate L.E. Danford ordered barrels of flour jettisoned from the port side to counter the list. Just before dawn, the wind reached gale force, and seas began to pour through Tarpon’s bulkheads.

Roustabouts were again sent below to jettison more cargo. The crew began to realize that the ship could not be righted. Less than 10 miles from shore, Tarpon had begun to sink. When Barrow finally gave the order to abandon ship, the vessel had already settled into the Gulf by the stern.

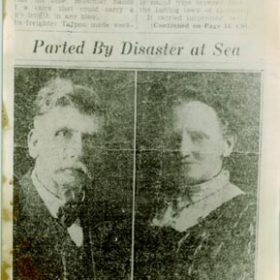

Those on deck were washed away, including Tarpon’s 81-year-old captain. Survivors floated alongside their drowned shipmates.

As the weather cleared, oiler Adley Baker sighted land in the distance and swam for it. He finally staggered ashore west of Panama City, after spending 25 hours in the water.

A passing motorist picked Baker up and drove him to Panama City, where news of Tarpon’s sinking quickly spread.

The Coast Guard dispatched a search plane and two ships to the scene to look for survivors. Of those rescued, some had been in the water over 30 hours. Eighteen people are believed to have lost their lives.

In 1938, divers salvaged the anchor from the Tarpon.

The anchor was purchased by Frank Burgduff the owner of the newly opened Old Dutch Road House and Tavern.

The old anchor remained as the centerpiece on the mantle of the Old Dutch’s massive fireplace for almost four decades.